In the 21st century, American Indians have continued to struggle with the “white man” taking their sacred lands, and tribal leaders have come forward to negotiate, protest, and attempt to save the land and water essential to the preservation of American Indian reservations

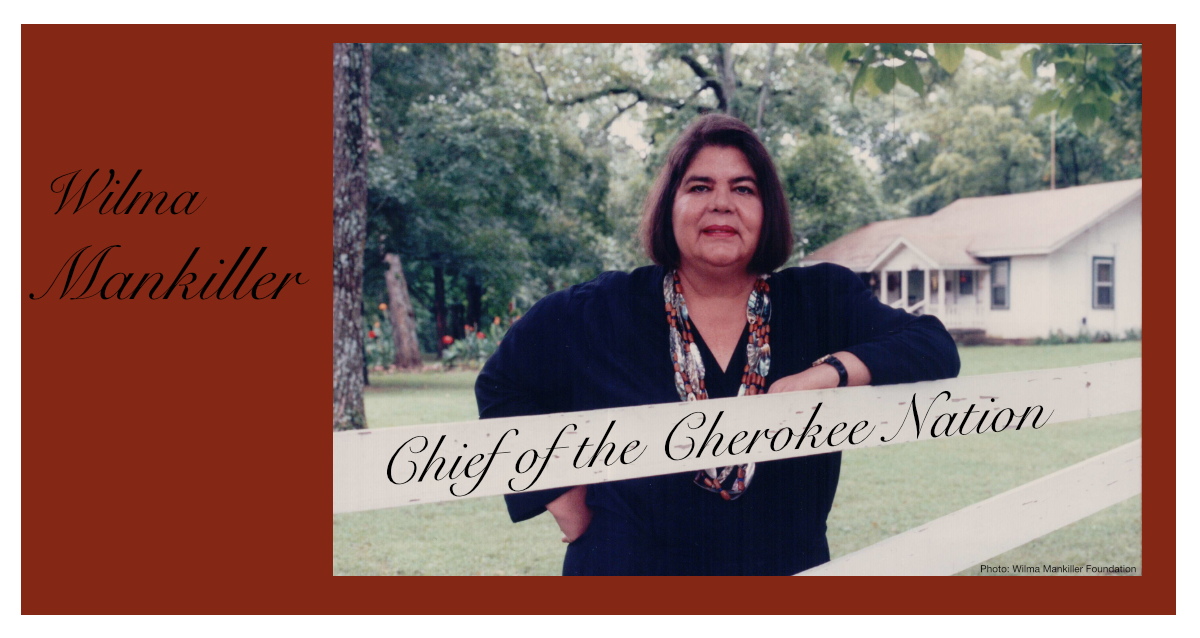

One such leader was Wilma Mankiller, the first woman to be chief of a major Native tribe, the Cherokee Nation. Wilma’s surname in Cherokee stands for a high military rank, such as a colonel or major, and was passed down from a Cherokee ancestor. In 1945, she was born on Mankiller Flats in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, which was land granted to her grandfather when the Cherokee Nation was forced to leave the mountains of Tennessee and the Carolinas and relocate to Oklahoma with the Trail of Tears in the 1830s.

During most of her childhood, Wilma’s family struggled to make a living farming. Their family home was without electricity and indoor plumbing; however, Wilma never realized her family lived in poverty. In 1956 when Wilma was 11 years old, the family moved to San Francisco as part of a Bureau of Indian Affairs project that attempted to move Indians off federally subsidized land by promising them jobs in big cities. Her father became a warehouse worker and union organizer, and Wilma was introduced to the power of organizing for political purposes.

Even though Wilma married at the age of 17 and had two children in her early twenties, she enrolled in college and studied sociology. Eventually, she became a social worker, but in 1969, an event occurred that brought her back to her Indian heritage. A group of American Indians took over the abandoned Alcatraz penitentiary and claimed it by “right of discovery.” The takeover was an attempt to bring attention to the suffering of American Indians and the government’s continual attempt to drive Indians off their land. Wilma joined the sit-in , realizing that this was one way “to let the rest of the world know that Indians had rights too.”

Alcatraz and the women’s movement of the 1960s motivated Wilma to help the American Indian community near San Francisco. Wilma became director of Oakland’s Native American Youth Center, motivating young people to be proud of their Indian heritage. And she joined with the Pit River Tribe group that fought against Pacific Gas and Electric when the company attempted to take over millions of acres of tribal land. Wilma learned how to exercise tribal sovereignty and treaty rights and used this knowledge again later when she returned to Oklahoma.

In 1976, Wilma decided to move back to Mankiller Falls with her two daughters. She found work as an economic stimulus coordinator for the Cherokee Nation and brought with her the activism and knowledge she had practiced in California. She used her grant writing skills as a way to successfully bring money to her community.

Within a few years, she saw another way to help her community and was hired as Director for the Community Development Department for the Cherokee Nation, which worked on providing water and housing to communities in need. Her first project organized 200 families in Bell, Oklahoma, to work together to build a 160-mile waterline to bring water to the community. Wilma knew that when people work together, unsurmountable tasks get accomplished. This project was featured in the movie, “The Cherokee Word for Water.”

In 1985, Wilma was elected Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation. During her 10-year tenure as Chief, she worked with the U.S. government to set up a self-government agreement with the Cherokee Nation and the EPA. Using profits from gaming, factories, and natural resources, she opened three rural health centers, expanded Head Start programs and improved educational access for all children, established drug prevention centers, and increased access to housing. Wilma realized she was not only in charge of improving the economic wellbeing of the tribal members but also in charge of teaching and preserving Indian customs and traditions to the youth. As part of her legacy, she created the Institute for Cherokee literacy and helped to found Women Empowering Women for Indian Nations. Near the end of her time as chief, Wilma oversaw a budget of $150 million a year, which included money from factories, gaming, hospitality, natural resources, and the federal government.

In 1998, President Bill Clinton awarded Wilma the Presidential Medal of Freedom. When Wilma died at age 64 from pancreatic cancer, her dear friend Gloria Steinem was by her side. President Barack Obama said that Wilma “transformed the Nation-to-Nation relationship between the Cherokee Nation and the Federal Government and served as an inspiration to women in Indian Country and across American.”

Mankiller: A Chief and Her People, 1993: an autobiography written with Michael Wallis

britannica.com/

www.okhistory.org/