Fannie Lou Townsend Hamer was the youngest of 20 children born into a sharecropping family in the Mississippi Delta. From the age of six, she worked in the fields, and at age 12, she left school to work full time and help support her family. Fannie continued working as a sharecropper on a cotton plantation near Ruleville, Mississippi, when she married Perry Hamer at age 27. The plantation owner recognized that Hamer had more education than the other sharecroppers and assigned her the job of plantation timekeeper since she could read and write.

At age 44, Hamer was stuck in a life of limited opportunities, but civil rights activists were working in her area, and Fannie noticed that. In 1961, she needed surgery for a uterine tumor, and a white doctor performed a hysterectomy without her permission. This was a common occurrence in Mississippi (known as the Mississippi appendectomy) at that time to prevent Black women from having children. Fannie and Perry were devastated and adopted two daughters.

Later that year, Hamer decided to fight back against the injustice toward Black people and attended a meeting of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee led by civil rights activists James Forman and James Bevel who were trying to register Black people to vote. In 1962, Hamer went with a busload of 17 volunteers to the county courthouse to sign up to vote. Their bus was stopped by police, and they were threatened and fined but did not turn back. Fannie led the passengers in singing spirituals during the police stop and interrogation. At the courthouse, only Hamer and one other person were allowed to apply, but they were forced to take an unfair literacy test and were told that they failed it. Hamer challenged the registrar’s decision. Upon her return home, the plantation owner fired Hamer for trying to vote but told her husband he had to stay through the harvest to pay off the sharecropping debt. Fannie and her two daughters went to stay with relatives in another town. When her husband left the plantation in the fall, the plantation owner kept the family’s car and furniture, allowing them to take only their clothes. This spiteful action fueled more determination in Hamer, who saw this setback as an opportunity. She responded by saying, “They kicked me off the plantation; they set me free. It’s the best thing that could happen. Now I can work for my people.”

The SNCC had noticed Fannie’s willingness to challenge the registrar and the police who had harassed the busload of voters. They found Hamer and brought her to an SNCC conference in Nashville in the fall of 1962. After getting to know Fannie, the SNCC offered her the job of community organizer, which paid a stipend of $10 per week. This was the family’s main source of income at that time.

In her work for the SNCC, Hamer organized voter registration drives, took people to the polls, and set up relief efforts. Numerous times, she and other activists were arrested and beaten, but that did not stop them. Fannie sustained permanent kidney damage from a beating in a Winona, Mississippi, jail in 1963. After leaving the jail in Winona, Fannie learned that Medgar Evers had been assassinated in Mississippi the previous day.

The summer of 1964, known as Freedom Summer, was a busy one for Fannie. She convinced hundreds of college students, both black and white, to travel to Mississippi to work for civil rights. Hamer felt the movement should be integrated and responded to objections by saying “If we’re trying to break down the barrier of segregation, we can’t segregate ourselves.”

Fannie was also busy that summer trying to reform the Democratic Party in Mississippi. While students talked to people and passed out literature, Fannie set up the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party to oppose the state’s all white delegation to the Democratic Convention. She ran for Congress that year and lost the primary, but her actions and interviews were televised despite the national Democratic Party’s and President Lyndon Johnson’s efforts to keep her off television. President Johnson wanted the Southern Democrats’ support for his bid for re-election and held a press conference to stop convention coverage and Fannie’s interview, but Fannie’s speech was heart wrenching and compelling, and many networks broadcast her story of the family’s eviction from the plantation and her beatings and arrests since that time. This included the night when white supremacists in her hometown shot 16 bullets into the house where she stayed with her friends fighting for civil rights. Fannie’s interview made Americans aware of voter suppression and brutality against civil rights activists in Mississippi. Five years later, Hamer was a member of Mississippi’s first integrated delegation to the Democratic Convention.

After the convention, Hamer traveled extensively as a civil rights speaker, raising money for the movement; however, her heart remained with her people in Sunflower County, Mississippi. In 1967, she was instrumental in lawsuits that led to many Black residents being allowed to register and vote in her county, and she assisted plaintiffs in a school desegregation lawsuit. Hamer realized that racial equality and wealth were created by business opportunities. She set up organizations such as a “pig bank” to give free pigs to Black farmers and the Freedom Farm Cooperative to help minorities own and farm land cooperatively. Donors such as Harry Belafonte gave her money for the land and buildings, which included stores where families could shop. In Ruleville, she arranged for 200 units of low-income housing to be built so families had a place to live and work on this cooperative. In the 1970s, the FFC was one of the largest employers in Sunflower County.

In her national work, Fannie focused on women’s issues by arranging family services and childcare for all races. This included helping to set up Head Start programs for low-income families. She believed that women should be involved in politics, and in 1971, she helped to set up the National Women’s Political Caucus.

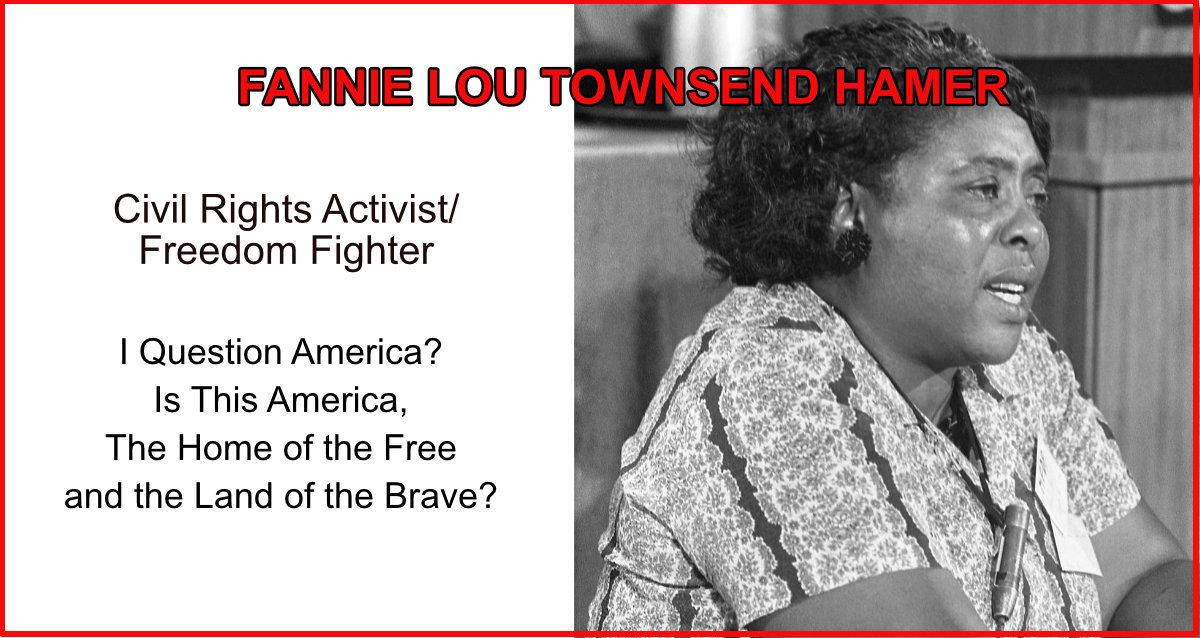

Fannie passed away in 1977 at the age of 59. The civil rights beatings, early poverty, heart issues, and a cancer diagnosis led to her early death. Hundreds of local residents and civil rights leaders attended her funeral and spoke of her devotion to her family, her local community, and the national Civil Rights Movement. Fannie is remembered for a quote from her famous interview at the Democratic convention where she stated: “If the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?” Her words are as true today as they were then. We must carry on as Fannie did to bring equal rights to everyone.

www.women’shistory.org/fannielouhamer

www.pbs.orgSee the Women in American History collection

https://www.biography.com/activist/fannielouhamer

https://www.womenofthehall.org/fannielouhamer

https://dakotacenter.org/Home/News/Fannie Lou Hamer

https://www.history.com/topics/fannielouhamer

https://time.com/History/Opinion/fannielouhamer